Lasers in Treating Keloid Lesions: Can The Treatment Be harmful To some Patients? Results of an online survey

Michael H. Tirgan, MD

ABSTRACT

Background: Lasers in Treating Keloid Lesions are among the most commonly used tools in the daily practice of dermatology. Although there are several reports about the utility and efficacy of laser treatment in keloid lesions, there is a paucity of literature as to how keloid patients perceive the efficacy of this modality.

Objective: To assess patients’ perception of the efficacy of lasers in the treatment of keloid lesions.

Material and methods: The underlying survey study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). An online keloid survey was launched in November 2011. Survey participants were asked to provide answers to numerous questions about their keloid disorder, including their perception of the efficacy of lasers for the treatment of their keloidal lesions. Descriptive statistics are provided.

Results: As of November 18, 2018, a total of 1,671 individuals had participated in this survey. Of those, 194 participants indicated that they had received at least one laser treatment for treatment of their keloids; among those, 177 provided an assessment of the benefit of this intervention. Five participants (2.8 %) reported that laser treatment cured their keloids; 47 participants (26.6%) reported having benefited from the treatment; 88 participants (48.0%) reported no improvements; but most interestingly, 40 participants (22.6%) reported that laser treatment caused worsening of their keloids.

Conclusions and Relevance: With several limitations, this study represents the first step in developing a patient-reported measure of treatment success and benefit from laser treatment. The most important finding of this study is that 22.6% of the study participants reported worsening of their keloids with this treatment. Worsening of keloids after laser treatments has not yet been reported by others.

INTRODUCTION

Lasers in Treating Keloid Lesions Laser devices have become an integral component of modern dermatology practice with an ever-expanding number of indications, including treatment of keloid lesions. In 1984, Apfelberg et. al. published one of the first studies on lasers in the treatment of keloid lesions (1). Ablative argon and carbon dioxide (CO2) lasers were used to excise well-established keloid lesions of the trunk or earlobe in 13 patients. The multiple-bore-hole argon technique and total excision with the CO2 laser were attempted. The authors reported that one patient with an earlobe keloid responded to treatment and keloids in all other patients showed no improvement. In the same year, Abergel and colleagues published their experience with eight keloid patients treated with a neodymium-yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Nd:YAG) laser in a nondestructive manner (2). With a three-year follow-up, the authors indicated lasting flattening and softening of the lesions, suggesting that the Nd:YAG laser was an effective treatment modality for keloids.

In their 1989 report, Stern et al. presented their results on the effectiveness of CO2 laser excision of earlobe keloids. Twenty-three keloids were excised by laser in 18 patients who were then followed for two years. With 17 recurrences, nine occurring between six and 12 months postoperatively, the authors concluded that they failed to demonstrate a lower recurrence rate of earlobe keloids using the CO2 laser. In the same year, Apfelberg et al. also reported on CO2 laser removal of keloids in seven patients with nine keloids located on the trunk, nuchal region, back, and earlobe (4). Eight of the nine keloids recurred to their original or close to original size as early as 10 months and as late as 22 months following laser intervention. The authors concluded that the long-term benefits of keloid excision with the CO2 laser was not demonstrated in their case study series.

Fast-forwarding 25 years, more recent studies show similar results. Mamalis et al. in their 2014 review of literature were left to conclude that the evidence was lacking to show efficacy of lasers, in part due to the paucity of adequate studies (5). Also in 2014, Koike reported on their experience using 1064 nano-meter Nd:YAG laser in 64 patients with keloids on the anterior chest (triggered by acne), upper arm (triggered by vaccination), or scapula (triggered by acne), and 38 patients with hypertrophic scars (6). The average number of treatments to the keloid lesions were reported to be 10 to 11. A complex scoring system was used to report response to treatment. The authors reported a few cases of dramatic responses in keloid lesions, however they concluded that “hypertrophic scars responded significantly better to 1064 nm Nd:YAG laser treatment than keloids. Keloid recurrence occurred when there was remaining redness and induration, even if only a small part of the scar was affected.”

An IRB approved online keloid survey was launched by the author in November 2011 to inquire into different aspects of keloid disorder, including the efficacy and potential side effects of various treatment modalities. The author hereby reports on patients’ reported outcomes among 194 survey participants who had been treated with lasers. To the author’s knowledge, this is the largest study ever conducted about the efficacy – or lack thereof – of lasers in the treatment of keloid lesions.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

A comprehensive questionnaire was developed to survey a large cohort of consecutive, unselected patients with keloid disorder. The study was initially approved in November 2011 by the IRB of St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital in New York. The study was subsequently transferred to and approved by Western IRB (WIRB 963770-1) as an exempt study meeting the exemption criteria under 45 CFR §46.101(b)(2) and 45 CFR 46.101(b)(4). Lasers in Treating Keloid Lesions

Study participants were asked to access the study questionnaire by visiting the study website, www.KeloidSurvey.com. After downloading and reviewing the study consent form, adult patients were asked to acknowledge the informed consent electronically. Parents were able to consent and complete the survey on behalf of their underage children. The survey posed numerous questions to the patients, assessing multiple variables such as age, ethnic background, family history, the extent and distribution pattern of keloid lesions prior to treatment, and response rates.

Participants’ access to the survey tool was limited to one access per computer IP address. Participants were also allowed to skip answering questions, either because the question did not apply to them or because they chose not to answer.

The author reports results of the survey patients’ perceptions of the benefit they might have gained from laser treatments. The study dataset was accessed on November 18, 2018. Descriptive statistics are presented.

RESULTS

Lasers in Treating Keloid Lesions The study was opened for accrual on November 14, 2011. As of November 18, 2018, a total of 1671 individuals participated in this survey. One hundred and ninety-four adult participants indicated that they had previously received laser treatment for their keloids; among those, 189 disclosed their gender: 54 (28.6%) were male and 135 (71.4%) were female

Age

Participants were asked to provide their age. Most participants were between ages of 18 and 45. Figure 1 depicts participants’ age at the time they took the survey.

Figure 1: Participants’ age distribution.

Age of onset of keloid disorder

Participants were also asked to record the age they developed their first keloid lesion. Peak age of onset among all participants was 16, with most developing their first keloid between the ages of 5 and 25. Figure 2 depicts participants’ reported age at the time they developed their first keloid lesion.

Figure 2: Age of onset of keloid disorder among the study population.

Country of Birth

A total of 190 participants provided information about their country of birth. Most (57.9%) were born in the United States, 5.8% were born in India, 3.2% were born in United Kingdom, 3.2% were born in Canada, and 2.6% were born in Philippines. Figure 3 depicts the country of birth for all study participants.

Although this distribution pattern correctly represents the country of birth of those who participated in this study, it is by no means a true reflection of the epidemiology of keloid disorder and is most likely a reflection of the level of healthcare services that might have been available to the patients. Furthermore, this information does not take into consideration the migration patterns or the patients’ country of residence.

Figure 3: Country of birth of the study participants.

Ethnicity

Participants were asked to provide their ethnic background. A total of 190 participants provided this information. Figure 4 shows percentages for different ethnic characteristics. Although this information is a correct representation of those who participated in this study, it is not a true reflection of the ethnic epidemiology of keloid disorder.

Figure 4: Participants’ ethnic background.

Pattern of Distribution of Keloid Lesions

Participants were asked to provide detailed information about the distribution of keloid lesions throughout their skin. Chest, shoulders, ears, and upper arms were the most frequently involved areas. Figure 5 depicts the distribution patterns of keloid lesions among the study participants.

Figure 5: Location of keloids. Participants were asked to choose all answers that applied to them.

Appearance and Shape of Keloid Lesions

Participants were asked to describe the shape and the appearance of their keloid lesions. To facilitate their answers, a reference image guide was provided online. As shown in Figure 6, nodular, linear, and flat keloids were the most common forms of keloidal lesions. Among participants, 26.6% considered their keloids to be massive, with keloid lesions occupying large areas of their skin.

Figure 6: Shape of keloid lesions. Participants were asked to choose all answers that applied to them.

Size of keloid lesions:

Participants were asked to describe the size of their individual keloid lesions on their skin. To facilitate their description, a comparison reference guide was provided on the questionnaire. Figure 7 depicts the distribution patterns of the size of keloid lesions.

Figure 7: Size of keloid lesions. Participants with several keloid lesions were asked to choose all answers that applied to them.

Triggering factors

Participants were asked to provide information about the factors that triggered their keloid formation, with 178 providing answers. Figure 8 shows the frequency of various triggering factors within the study population. Acne was by far the most common triggering factor, followed by skin injury and surgery. Fifteen percent of participants listed vaccinations and 13% listed chicken pox as the triggering factor in their keloid development.

Figure 8: Triggering factors. Participants were asked to choose all answers that applied to them.

Laser Treatments

Participants were asked to report the total number and frequency of laser treatments that they received. Figure 9 depicts the number of laser treatments and the frequency of treatment is reported in Figure 10. It is interesting to note that a large number of participants reported receiving only one or two laser treatments. Only 11.4% reported more than 10 treatments. Most participants reported a monthly schedule of receiving treatment.

Figure 9: Number of laser treatments.

Figure 10: Frequency of laser treatments.

Efficacy of Laser Treatments

The efficacy of Lasers in Treating Keloid Lesions was assessed by asking participants to provide only one answer to three sets of multiple-choice questions that explored observed efficacy, overall assessment of benefit from treatment, and durability of response to treatment.

When asked about response to treatment, only 4% of participants reported complete resolution of their keloid lesions with laser treatment.;10% reported significant improvement in the appearance of their keloids; 32% reported slight improvement; and most importantly, 54% reported no response to laser treatment. Figure 11 shows the reported response rates to the laser treatments.

Figure 11: Reported response rates to laser treatment.

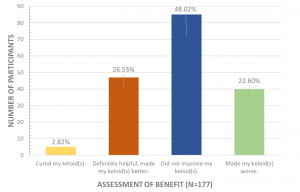

When asked about the benefit derived from laser treatment, only 3% of participants equated their benefit to cure of their keloid lesions; 27% reported that laser treatment improved their keloids; 47% reported no improvement; and 23% reported that laser treatments actually made their keloids worse.

Figure 12: Participants’ assessment the benefits of keloid treatment.

Durability of Treatment Results

When asked about durability of laser treatment, of the 176 participants who provided an answer to this question, 10% reported permanent and durable benefit, 6% reported durability of more than one year prior to recurrence of the treated keloid lesion(s). Figure 13 depicts the durability data collected from participants.

Figure 13: Participants’ assessment of durability of treatment.

FACTORS DETERMINING THE RESPONSE RATES

Various dataset comparisons were performed to identify factors that could have contributed to the response to laser treatments. Comparisons were made between the group who reported responding to laser treatment and those who either reported no response to the treatment or a worsening of their keloids after laser treatment. Participants’ age, age of onset of keloid disorder, number of laser treatments, and shape and size of keloids did not appear to correlate to response to treatment. This analysis only suggested a negative correlation between acne as a triggering factor for development of keloid lesions and the response rate to laser treatment.

Figure 14: Analysis of triggering factors and the response rate to laser treatment between two groups, those who reported responding to treatment and those reported no response to treatment.

ROLE OF ETHNIC SKIN TYPE:

To explore the role of ethnic skin type on treatment outcome, the source data was re-analyzed to determine whether the ethnicity might have played a role in either response to laser treatment or side effects. As of 9/3/2019, among the participants, 39 African Americans, 39 Asians, and 65 Caucasians (White American – European) had undergone laser treatments. Table 1 provides a summary of the response to treatment as well as assessment of benefit from laser treatment according to the ethnic background. Analysis of the data showed that African Americans reported a higher rate of worsening of their keloids (36%) when compared with Asians (18%) and Caucasians (16%).

Table 1: Role of ethnic skin type in response to treatment and potential to worsen keloid

| Ethnic Background | African American | Asian | Caucasian | |

| Sample Size | n=39 | n=39 | n=65 | |

| Response to Treatment | (n=32 – Skipped=7) | (n=39 – Skipped=0) | (n=57 – Skipped=8) | |

| Completely Resolved | 4 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Significant Improvement | 1 (3%) | 6 (15%) | 5 (9%) | |

| Slight Improvement | 7 (22%) | 17 (44%) | 18 (32%) | |

| No Response at all | 20 (63%) | 16 (41%) | 34 (60%) | |

| Assessment of Benefit | (n=33 – Skipped=6) | (n=38 – Skipped=1) | (n=57 – Sipped=8) | |

| Cured my keloid | 2 (6%) | 0 | 0 (0%) | |

| Definitely helpful | 3(9%) | 15 (40%) | 15 (26%) | |

| Did not improve | 16 (48%) | 16 (42%) | 33 (58%) | |

| Made my keloids worse | 12 (36%) | 7 (18%) | 9 (16%) |

DISCUSSION

Lasers in Treating Keloid Lesions Lasers are used to either remove (ablative) or to treat (non-ablative) a keloid lesion. Ablative lasers, such as the CO2 laser, emit beams that are absorbed by water molecules in the skin, making them ideal for precise surgical ablation and concomitant photocoagulation and hemostasis (7). Non-ablative lasers such as the Nd:YAG laser emit beams that are absorbed by hemoglobin or melanin and are thought to cause selective damage to blood vessels of the target tissue; therefore, it has been hypothesized that non-ablative lasers may interact directly with the biological function of keloidal tissue (6, 8).

However, not all keloid lesions will respond equally to laser or other forms of treatment. Despite the global availability of lasers, only a few studies have examined the efficacy of lasers in the treatment of keloid lesions. Furthermore, several of these studies have included patients with hypertrophic scars, thereby making an analysis of the response rate among keloid patients very difficult (8-9).

The large sample size of the current study – 194 participants with keloid disorder – makes it the largest study ever conducted and published about the efficacy, or lack thereof, of laser treatments in keloid patients. It is also the first ever published report of the patients’ perception of the efficacy of lasers in the treatment of keloids. The study’s large sample size allowed for analysis of potential correlations between response rate and a multitude of clinically significant variables such as ethnic background, gender, age, size, and number of keloid lesions.

The study has several limitations. It is not a random survey of patients with keloid disorder. Moreover, the survey was biased towards those searching the Internet for information related to their illness, or subjects exploring treatment options for their illness with possible over-representation of younger and more computer literate individuals. Since the survey was conducted in English, it likely excluded non-English speaking individuals. The survey was also unable to collect data on type and other specific details of laser devices and modalities used. Lastly, the survey tool was not validated. Nonetheless, this self-selected group of respondents provided a glimpse into the real-world experience with laser treatment, and their perception of the efficacy – or lack thereof – of this intervention.

In contrast to the published literature in which the investigators generally report a positive assessment of laser treatment on keloids [6], this study indicates that approximately 30% of the participants found laser treatment to be effective. Even when effective, the efficacy of this treatment modality was not durable and faded over time. Only 28% of participants saw treatment efficacy lasting more than three months, and nearly 72 % reported either none, or minimal benefit that lasted only one to three months.

Most importantly, and for the first time, this study reveals that laser treatments can actually be harmful to some patients and result in worsening of the keloids.

Notably, 24.6% of the participants received only one laser treatment and another 24.6% received only two treatments. Although the survey did not collect data as to the compliance and why the treatment was not continued, one can speculate that the treatment was either very effective or possibly un-affordable, or it was potentially harmful.

The fact that only some patients benefited from laser treatment argues in favor of existence of different subsets of keloid lesions, some of which may be sensitive to lasers and do respond to this treatment and some that are resistant to treatment with lasers. The mechanisms involved in keloid sensitivity or resistance to laser treatments are not known.

CONCLUSION

Although this study has several limitations, however, its large sample size provides us with an opportunity to question the true efficacy, or lack thereof, of laser treatments in treating keloids. This real-world experience revealed that laser treatment was effective in only 30% of keloid patients and led to the worsening of keloids in approximately 23% of patients, a new finding that to the author’s knowledge has not been previously reported. Lasers in Treating Keloid Lesions

Patients’ perceptions of the benefit – or lack thereof – of any treatment modality can impact compliance with the treatment. False expectations are likely to result in patients’ disappointment.

Patient-reported outcomes shall be integrated in all keloid treatment studies. Investigators shall work together to design and validate reliable tools that can be used in future keloid research.

The author hopes that this study will be an impetus to plan and conduct a properly designed prospective study, or to perform a retrospective data analysis from centers where long-term follow up outcome data is available.Lasers in Treating Keloid Lesions

REFERENCES

1- Apfelberg DB, Maser MR, Lash H, White D, Weston J. Preliminary results of argon and carbon dioxide laser treatment of keloid scars, Lasers Surg Med. 1984;4(3):283-90.

2- Abergel RP, Dwyer RM, Meeker CA, Lask G, Kelly AP, Uitto J. Laser treatment of keloids: a clinical trial and an in vitro study with Nd:YAG laser, Lasers Surg Med. 1984;4(3):291-5.

3- Stern JC, Lucente FE, Carbon dioxide laser excision of earlobe keloids. A prospective study and Jordan C. critical analysis of existing data. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 989;115(9):1107-1111.

4- Apfelberg DB, Maser MR, White DN, Lash H. Failure of carbon dioxide laser excision of keloids, Lasers Surg Med. 1989;9(4):382-8.

5- Mamalis AD1, Lev-Tov H, Nguyen DH, Jagdeo JR. Laser and light-based treatment of Keloids–a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014 Jun;28(6):689-99.

6- Koike S, Akaishi S, Nagashima Y, Dohi T, Hyakusoku H, Ogawa R. Nd:YAG Laser treatment for keloids and hypertrophic scars: an analysis of 102 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2014;

7- Azadgoli B, Baker RY. Laser applications in surgery. Ann Transl Med. 2016 Dec;4(23):452.

8- Alster TS, Handrick C. Laser treatment of hypertrophic scars, keloids, and striae. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2000;19:287–92.

9- Bouzari N, Davis SC, Nouri K. Laser treatment of keloids and hypertrophic scars. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:80–8.